Damascus Umayyad Mosque

Syria Damascus 10,11,12,13,14,15th Century

Umayyad, Seljuk, Ayyubid, Mamluk, Ottoman

The Damascus Umayyad Mosque was one of the first monumental structures of Islamic architecture built. it was constructed in Damascus during the Omayyad caliphate.

The area where the Umayyad Mosque is situated has been a sacred site tor thousands of years. Archaeological excavations have uncovered the oldest architectural remains, belonging to the Aramaic period, and which were dedicated to the god Hadad. The Temple of Hadad was converted into a temple of Zeus and Jupiter in the Hellenistic and Roman periods respectively. This temple became a church in the 4th century. The church was enlarged to become a cathedral, dedicated to St. John. After Damascus was conquered by the Muslims, they began to share the use of the building far worship with Christians during the reign of the Omayyad Caliph Muawiyah bin Sufyan. The Muslims used the eastern part of the building, and the Christians used the western part of the building tor worship. This joint use continued far an extended period. However, when the number of Muslims increased, the section dedicated tor the Muslims became insufficient. Furthermore, in view of the need far its own architectural style, a new arrangement needed to be envisioned far the mosque.

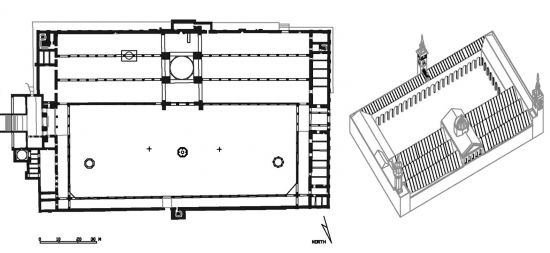

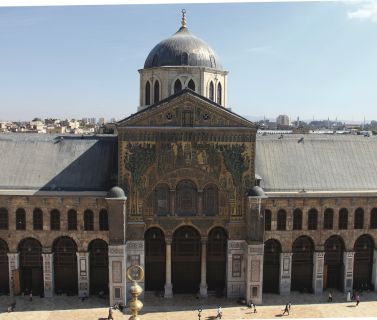

During the reign of the Caliph Walid, a meeting was held between the Muslims and the local Christian leaders. This meeting guaranteed that other churches would not be converted into mosques, and exacted a promise to build a new Church of the Virgin Mary far the Christians in exchange far the exclusive use of this site by the Muslims far a new mosque. When the church was removed and the construction of the new mosque began, an architectural style, in accordance with Islamic practices, was implemented. The design scheme established far this mosque would contribute to the design of future mosques. The plan of the mosque consisted of a rectangular, central courtyard and a sanctuary section in the southern part. The sanctuary consisted of three naves, parallel to the sanctuary wall. There was a nave, perpendicular to the sanctuary, in front of the sanctuary. The nave in front of the sanctuary opens onto the courtyard via three doors. The flooring inside the building was repaired and renovated many times. The relationship of the naves to each other became altered due to these renovations. Original floor coverings, belonging to the Omayyad period, were uncovered during the most recent restoration.

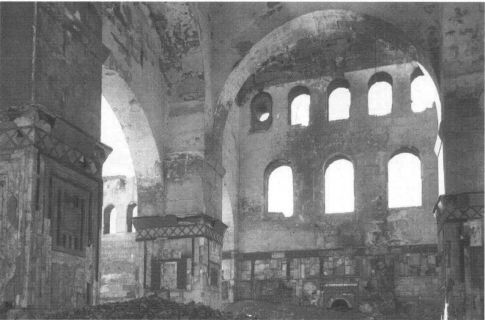

There are three domed sections in the courtyard of the mosque. One of them is a ritual ablution fountain area, the other one is the Treasury room and the third one is the Zeynel Abidin dome, with eight columns. Various stone columns and types of masonry can be seen in the courtyard of the building. The arcade, with double columns, in the northern part was complete!y destroyed during the 1759 earthquake and was renovated without columns in the Ottoman period. The columns, in a row parallel to the mihrab wall in the sanctuary, have column capitals of the Corinthian order. Each support row is bilevel. The arches of the first level are semi-circular and the second level has ogee arches with double radii. The main nave is a tall, central space, and is higher and wider than the other naves. There is a large Nisr (Eagle) dome in the middle. There were four inscriptions on the pilfars which support this dome. Today, these inscriptions are in the Damascus National Museum. The inscriptions state that the Seljuk Sultan Malik Shah ordered the construction of the dome. According to this, the dome was probably commissioned by Sultan T utııs, in the name of his brother Malik Shah.

There is a small building, made of marble, to the east of the sanctuary. This is the grave of St. John or the Prophet John, as he is called in the Qur'an. The outer walls of the mosque are from the Roman period, when it was used as a temple. The towers in the comers of the building also date from from the Roman era. Two of the towers were repaired during the reign of Caliph Walid. They became the bases of the minarets in this section. A third minaret is known as the Aruz minaret. The central portion of this minaret was erected by the Ayyubids after a fire in 1174. The minaret to the east is known as the Jesus Minaret. This minaret was damaged during an earthquake in 1759 and was renovated in the Ottoman period. it is recorded on its inscription that the minaret in the east was renovated in 1488, after the conquest of Timur in 1401. There are varied decorations inside the building. These include marble carvings and mosaics on the walls and multi-colored mosaics. Design elements include geometric and vegetal motifs and depictions of landscapes. These elements cover the arcade surfaces of both the interior and the exterior of the sanctuary section. The images include depictions of landscape scenes of the city of Damascus, such as the Barada River. Marble panels were mounted on the wall through hooks in small holes. Because some of the marble parts were broken or damaged, they were subsequently covered with blue and white glazed üles in the Ottoman period.

Translation of the inscriptions (Translation: Mehmet Tutuncu)

1: "l-4 in the name of the Compassionate and Merciful God. Kuran 111 18-19 (Until lslam} 18. God, angels and the enlightened ones testify that there were no gods other than Him. There are no Gods other than God. He has absolute power, command and wisdom. 19. Islam is the religion of God in times without a doubt. This dome, maksoorah, ceiling, windows and columns were commissioned by the Great Sultan, Master of great Shahs, our master, master of sultans, Conqueror Muhammad's son Malik Shah and his brother, and esteemed victorious person, helped by God, Crown of the state, pride of the nation and Honor of the people, son of the Islamic emperor and son of the helper of believers, Abu Said Tutus and esteemed Sheikh Nizam al-Mulk Atabeg Abu Ali Hasan bin Ali and esteemed vizier Fahrulmaali nash-ud-devle, assistant of the two emperors, Abu Nasr Ahmed bin el Fazı, to acquire merit in God's sight, using their own wealth in the months of 475, when the Abbasid caliph imam Muktedi-bi-emrillah was the emir of the believers."

2: "in the name of the Compassionate and Merciful God. Kuran IX 40. lf you do not help Him (the Prophet} (you know} that when those who denied him took him as one of the persons out (of Mecca}, God helped him himself.

They were in the cave. "Don't be upset, because God is with us," he said to his friend. God gave him trust and peace and supported him with annies; you cannot see and thus humiliate the word of those, who denied him. God's word is the greatest. God has absolute power, command and wisdom. This dome, maksoorah, ceiling, windows and columns were commissioned by the Great Sultan, Master of great Shahs, our master, master of sultans, Conqueror Muhammad's son Malik Shah, and his brother, and esteemed victorious person, helped by God, Crown of the state, pride of the nation and Honor of the people, son of the Islam emperor and son of the helpers of believers, Abu Said Tutus and esteemed Sheikh Nizam al-Mulk Atabeg Abu Ali Hasan bin Ali and esteemed vizier Fahrulmaali nash-ucl-devle, assistant of the two emperors, Abu Nasr Ahmed bin el fazı, to acquire merit in God's sight, using their own resources, in the months of 475, when the Abbasid caliph imam Muktedi-bi-emrillah was the emir of the believers."

Sources state that there was another inscription, belonging to T utus, on the northern wall of Damascus Umayyad Mosque, facing east. However, this inscription has been tost. The following was written on the inscription:

"He ordered this wall to be built: Great esteemed malik, victorious Mansour, helped by God (aduddin}, Crown of the state, Pride of the Nation, Honor of the Believers, Abu Said Tutus, son of Islam Malik, assistant of the amir of the believers, Alparslan bin Muhammed bin Dawd, using his own resources in the months of 482."

Behrens-Abouseif, D., "The Fire of 884/1479 at the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus and an Account of its Restoration," Mamluk Stud. Rev., XVlll/1 , 2004, s. 279-297

Brisch, K., "Observations on the lconography of the Mosaics in the Great Mosque of Damascus," Content and Context of Visual Arts in the lslamic World, ed. P. P. Soucek (University Park, PA) Londra, 1988, s. 13-24 Creswell, K. A. C., Early Muslim Architecture, i Oxford, 1932; 2nd edn. in 2 vals, Oxford, 1959.

Finster,B., "Die Mosaiken der Umayyadenmoschee," Kunst Orients, Vll(l 970, s. 83-141

Flood, F.B., The Great Mosque of Damascus: Studies on the Makings of an Umayyad Visual Culture Leiden, 2001.

Grafman R. ve M. Resen-Ayalan, "The Two Great Syrian Umayyad Mosques: Jerusalem and Damascus," Muqarnas, XVI, 1999, s. 1-15.

Rihawi, Abdul Qader. Arabic lslamic Architecture in Syria. Damascus: Ministry of Culture and National Heritage,1979.